What does the world care about the Templar's order's destruction?

In 1782, duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, Grand Master of the Masonic order of the Strict Observance, sent a questionnaire to the lodges of his obedience when he convoked them to the general Convent in Wilhelsmbad. Amongst the questions sent out to them were the following:

- Did the order have for origin an ancient society, and if so, which one?

- Do «Unknown Superiors» really exist, and if so who are they?

- What is the final aim of the order?

- Is it to restore the Templar Order?

By his many questions, the Grand Master opened the way for the questioning of the Templar heritage of his order. Joseph de Maistre wrote back to him, giving his personal view: «What does the world care about the destruction of the Templar Order? Fanaticism created them, greed abolished them, that is all.»

Finally the duke of Brunswick gave up the templar denomination for his obedience, preferring to keep to the terms of Rectified Scottish Rite. We can however thank the duke of Brunswick for his passivity during the battle of Valmy , thanks to which the French declared the French Republic on September 22th 1792, giving all Louis XVI's subjects access to the status of citizens, free and equal in rights.

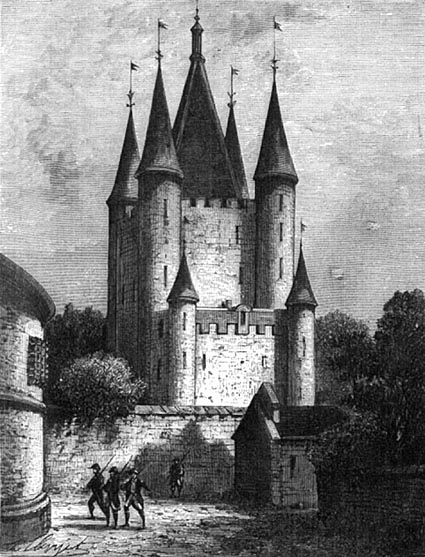

It is interesting to note that two events remain intimately linked in the history of France: the arrest of the Templars in 1307 and the proclamation of the Republic in 1792. By the irony of fate, the King of France Louis XVI was imprisoned in the tower of the former enclosure of the Temple of Paris before being decapitated.

This regicide was seen by many French citizens as a posthumous revenge for the martyr of the Grand Master of the Templar order, Jacques de Molay. Whatever Joseph de Maistre may have thought, history had kept the memory of the past centuries.

A knightood in the service of the Gregorian church

The destruction of the Templar Order marks the end in western history of the Gregorian church – named after Gregory VII (1073-1085), the first pope who dared to pronounce a definitive sentence of excommunication against an emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Having excommunicated Henri IV (1056-1106), the pope left it up to the Prince-electors to provide for the "salvation of the Republic" – which meant in his words to find another emperor.

Exasperated by the abuses and by the arrogance of the nobility, Pope Gregory VII had decided to free Christianity from its state of subjection and, to use a monastic formula, he wanted Christians to become “celestial citizens ”.

It is well-known that the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, more commonly known as the Templars, were charged by the Roman Church with safeguarding the Holy Land. What is less commonly known is that the knights, throughout the creation and defense of the new Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, were also fighting with the hope that one day we would all become citizens, sharing the same civic rights.

The Knights Templar, and more widely the Gregorian church from which this knighthood came wished to give us back our free will in a time when we were kept under the rule of divine right monarchy.

The Gregorian church came from the monastic world. Pope Gregory VII, son of a modest Italian journeyman, had himself been brought up in a Roman Benedictine monastery.

Gregory VII and the Gregorian church relied on the Augustinian theological tradition and on propagandists such as Bonizo de Sutrito to proclaim the superiority of the ecclesiastic institutions inspired from the senatorial institutions of the Ancient Roman Republic, and to deny to the Emperor and to all the Carolingian feudalism the right to invest bishops by the ring and crosier. This is what historians have called euphemistically the Investiture Controversy. It was not just an isolated dispute as its name would let us believe, it was a long-lasting dispute in which, each time the Roman bishops felt their authority threatened, they invoked the memory of the Roman Republic's institutions to assert their primacy over the Western world.

A powerful enemy: the Carolingian Church

Of course, the Catholic Church as a whole did not share this civic vision of Christianity. The Carolingian Church, in contrast with the Gregorian Church, got the support of Charlemagne's successors to chase the Gregorian popes out of Rome. The schism of the Catholic Church was unavoidable and an ideological war began between the Roman Churches. In this war between two Churches, symbols played a big part.

The Carolingian Church relied on the feudal nobility from which most of the Carolingian clergy came. Its day of glory was on Christmas day, in 800 A.D in Rome, when the King of the Franks, Charlemagne, received the crown from the hands of Pope Leo III (795-816), thus reviving the title of Western Roman Emperor.

By doing so, the Latin church and the Roman bishopric liberated themselves from the supervision of the Byzantine Empire. The Carolingian clergy gave to the event a quasi-messianic signification, in which the Holy Roman Emperor was identified with Christ Liberator, or more exactly, as the Clunisians said , a new 'Christ Recapitulator' . The consequences of this policy were to give a very marked sacerdotal character to the royal function and turn the Latin cross into a major symbol of the Carolingian civilization.

Faced with the Carolingian Church and its powerful feudal allies, the Gregorian Church was bound to disappear. The Gregorian pope Urban II (1088-1099), a former monk of Cluny, had to flee Rome and find shelter with his Norman allies while the Antipope Clement III, protegé of the Germanic emperor Henry IV, settled on the Holy See. Another Gregorian pope, Gelase II, a former monk trained in the Mont Cassin monastery, was persecuted by Frangipani, a roman nobleman on the Emperor's side: beaten by Frangipani's handymen just after his election by the College of Cardinals, harassed and hunted down on all sides by Frangipani's men, Gelase II died of exhaustion in exile exactly one year and four days after his election.

The initiative which insured the survival of the Gregorian church was Urban II's call for the crusade during the Gregorian Council of Clermont in 1095. The success of the resulting military expedition , the liberation of the city of Jerusalem without the help of any Carolingian monarch, established the Gregorian popes in the Holy See for a while – to the great displeasure of the Carolingian clergy. Let us keep in mind that the first crusaders were booed by the followers of the Antipope Clement III when they crossed Rome.

The two Crosses of Christ

In his exhortation to the Knights Templar , saint Bernard writes about those who are “elected in the Christ”. They form an army to liberate Jerusalem and to protect the Gregorian church . The 'elected ones' are all those who have answered to the call of Clermont and as in the Book of Isaiah, bear the sign of his“ authority is upon (their) shoulder” (Isaiah; 9,5)

But it is important to underline that this sign is not the Latin cross, the cross of the crucifixion, associated with the Carolingian church. It is the angels cross, in favor in the monasteries. This Greek cross is a symbol of spiritual life. Saint Bernard reminds the Templar Knights : “'The Spirit gives life; the flesh counts for nothing. The words I have spoken to you are spirit and they are life.' (John 6:63) . Moreover, he who finds life in the words of Christ, no longer seeks the flesh, he is one of ' the blessed who believe without seeing ' (…) as for the children or men who are like animals, taking in consideration the limits of their comprehension, he has the prudence to offer to them only 'Jesus and Jesus crucified.' (Saint Bernard, In Praise of the New Knighthood; 6;12)

It is a cross with equal arms that will be fixed on the shoulder of the crusaders gathered in Clermont, a star-shaped cross to guide the pilgrims in their journey to the Holy Land, where the Child Saviour was born for our greatest consolation.

A new liturgy for a new time

It is important to note that the Gregorian liturgy will also highlight different celebrations in the liturgical calendar. The Canons Regular of Saint Augustine for instance emphasize the liturgical period starting with the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, when the Christ announces the coming of the Paraclete – that is the spirit of consolation which manifests itself ten days later, on Pentecost. The Canon Regulars have the peculiarity of being clerics who live in community like monks.

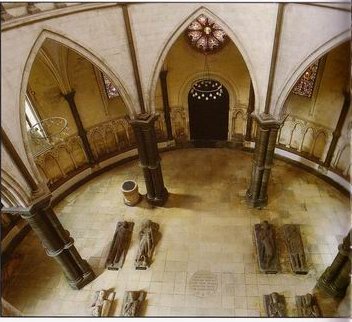

The Templar Knights Rule states that the knights will follow religious service according to the Canons customs. In London, the inauguration of the new Templar House in 1240 took place on the very day of The Feast of the Ascension. We can also notice in this commanderie of London that some of the recumbent statues of the Templar knights represent them laying with their legs crossed.

In the Canon Regulars symbolic language , the crossed legs represent the Roman numeral “X”, in reference to the ten days from Christ's Ascension and the Descent the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. Pentecost day, the day of the Paraclete, the spirit of consolation, will be the titular feast of the apostolic college. For the Canon Regulars, Pentecost will also be the feast day of the Cathedral Chapter – the birthday of the new Church.

A new mode of governance

In the Gregorian mind, the “consoled ones” were all those who, thanks to the new Latin kingdoms in the Holy Land, would finally get the right to speak up in chapter, and the Gregorian Church's policy was centered on this very goal: setting up the Chapter as a new place of temporal power.

In 1059 already, the Roman church had created the College of Cardinals, which, in violation of Carolingian law, seized the right to elect the Pope in the place of the Emperor. Building on the monastic tradition of electing the abbot of a monastery by the monks gathered in the chapter, the Gregorian church tried to generalize this practice to the chapter cathedral and enable the clercs to elect their bishop.

Through the impetus given by the Gregorian church, the place of the chapter institution in medieval governance gradually grew in importance. In 1114, the Cistercian Order created the General Chapter, a deliberative assembly commanding all the monasteries of the order – which was in a way a prefiguration of the present European Parliament. The Canons Regular of Saint Victor of Paris, very close to the throne, took up the General chapter institutions. Orders of chivalry such as the Knights Templar, would soon follow. Created in Jerusalem in 1119, the Knights Templar claimed to elect their Grand Master. The Carolingian monarchs felt the urgency of the threat because they knew that behind the chapter institution, which brought to mind the Senate of the ancient republics , the Gregorian church was tempted to spread this means of governance to the profane world.

Everyone knows that in that time, in the scriptorium of the monasteries, crabby monks copied romances about a supposed Round Table around which the knights and the king seated as equals . Already a kingdom of the West, the Plantagenet realm, seemed to be in accordance with the monks' vision.

A ruthless war between the Carolingian monarchs and the Gregorian Church was unavoidable. It would be a total war and would end in the kingdom of France as we know it.

by Jean-Pierre SCHMIT