The secret statutes of the Knights Templar

Presentation of the documents

Theodore Merzdorf, librarian at the ducal Library of Oldenburg, published in 1877 a German edition of documents providing from the archives of the Grand Masonic Lodge of Hamburg.

These texts, originally in Latin, are an official Rule of the Knights Templar followed by three other documents presented as the secret statutes of the order. They are presented as copies of authentic documents found in the archives of the Vatican in the 1780-1790s by a Danish scientist , Frederic Münter 3 .

These documents are as follows:

-

The official Rule, composed of seventy-two articles, with seven articles complementing the 'Regula' dated on St Felix's feast day, 1205, and transcribed by brother Matthew Tramlay. This rule is similar to other known copies of the Knights Templar Rule .

-

The second document dated August 1252 beginning with "Here begin the secret statutes of the Elected Brothers " consists of thirty articles approved by two dignitaries of the order, Roger de Montagu, Preceptor of Normandy, and Robert de Barris, Procurator.

-

The third document dated July 1240 opens with "Here begins the" liber consolamenti "or secret statutes, written by Master Roncelinus for the Consoled Brothers of the militia of the Temple”. These statutes, composed of twenty articles are signed by master Roncelinus and another dignitary of the Templar Order, brother Robert of Samford, Procurator of the Knights Templars in England.

-

The last piece dated August 1240 starts with"Here begins the list of secret signs that master Roncelinus has assembled in eighteen articles and addressed to the same Robert of Samford.”

Extract from Article 30 of the Statutes of the Elected Brothers :

"If a brother is dying (...) the deceased will be buried with his red belt, we will say for him the Mass of the Holy Spirit in red clothes and on the headstone will be engraved the oldest sign of salvation, the Pentalpha. "

Extract from Article 7 of the Statutes of the Consoled Brothers :

"Have in your houses large and hidden meeting places, which we can get to by underground corridors, so that the Brothers can attend meetings without fear of being bothered. "

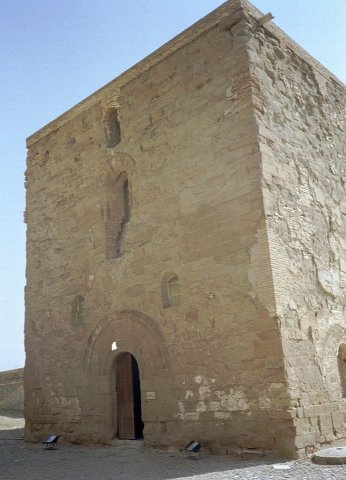

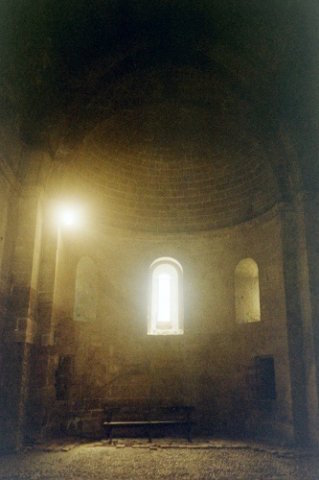

Entrance of the underground passage of the Templar church of the fortress of Monzon, meeting place of the chapter of the province of Aragon

the authenticity of documents questionned

The 'Masonic' provenance of the Hamburg articles , the sulfurous content of the 'secret statutes' and the fact that the translation was made from copies and not from original documents soon aroused suspicion of Professor Merzdorf's work.

The first criticisms came from Hans Prutz, a great German historian specialized in the orders of knighthood , in a book published in Berlin in 1879. 4 Amongst the various arguments put forth to expose the inauthenticity of the texts, echoed by Rene Gilles in his book « Are the Knights Templar guilty? » 5, Prutz argued that there can be no possible link between the doctrine comprised in the documents of Hamburg and the one of the minutes of the Templars trial.

Moreover, Prutz asserted that Islam didn't go along with any of the heresies in the Middle Ages. In addition, he said, many parts of the statutes were copied from the Bible, the Gospels, the exhortations of St. Bernard, and it was impossible that ignorant Templars knew these texts. Finally, Hans Prutz gave an indisputable argument by revealing an anachronism in the text: the word 'Druze' used in one of the articles would have been unknown to the chroniclers in the Middle Ages.

The documents unanimously condemned

This last point finished off Theodore Merzdorf's publication. His work was never translated into French, and it was not until 1957 that the articles of the “Secrete Rule” were first translated in French by Mr. Rene Gilles. Even today all historians except Rene Gilles agree to consider these documents as forgeries.

A new anachronism was even detected, proving once again the fraud. It seems that the forger by signing the statutes under the name of Master Roncelinus had copied a name mentioned during the trial of the Templars. During his questioning on November 15, 1307, concerning the perverse rituals in which the brothers forswore the Christ and spat on the cross , the Preceptor of Aquitaine and Poitou, brother Geoffroy de Gonneville, declared: « ... some say that it was one of the evil and perverse introductions of master Roncelin in the statutes of the order, others say it comes from the evil statutes and doctrines of Master Thomas Berard... »6 Now, the name of Roncelin reappears in the testimony of another brother, Guy Dauphin, who speaks of a "gentleman of Provence introduced within the order by Master William of Beaujeu" 7 in 1285. 8. This Roncelinus, identified as a knight of Provence called Roncelin de Fos 9 introduced in the order in 1285, couldn't have written the secret statutes in 1240.

Druze, Roncelinus : with these two anachronisms , the Hamburg documents were definitively ruled out.

the debate revived

In fact, these two proofs are void. We now know that the word « Druze » was mentioned in the account of a pilgrimage made by Benjamin of Tudela between 1163 and 1173. 10 Benjamin of Tudela did more than just mention the word, since he also described their customs. As for the Roncelinus issue, historians have found out that there was a master Roncelin in the Templar order at the estimated period of writing of the statutes.

Historians have indeed identified two Roncelin de Fos 11 in the Knights Templar. We already have mentioned the Roncelin de Fos who was introduced in the order at St. Jean d'Acre in 1285, probably as an affiliate member of the order since he married two years later with Mabille Agoult and became in 1310 Captain of the castle of Hyeres for Charles II of Anjou, King of Naples and Count of Provence.12

It is the other Roncelin we are interested in here. Although his biography is still imprecise, he appears in the Provence chronicles as early as 1237. 13 This knight was Master of Tortosa in 1242, Master of Provence from 1248 to 1250, then Master of England from 1251 to 1259, and again Master of Provence from 1260 to 1278 14 - date of his probable death. Therefore he could have been the signer of the text. He also could have known the other signatory, Robert de Samford, who was Master of England from 1241 to 1248 and again in 1259 15, in succession to Roncelin de Fos.

The debate concerning the authenticity of the secret rules is therefore revived.

seal used by Robert de Samford

a negative bias against the text because of its sulfurous tone

In some ways, the articles of the rules are so outrageous that it is hard for a modern reader to even consider the possibility of their authenticity.

The Article 18 of the Rule of the Elected Brothers says for example:

"The kingdom of God is within us. The Church of the true Christ changed at the time of Pope Sylvester into the synagogue of Antichrist, and St. Peter's Rome into a modern Babylon." 16

The aggressive tone towards the Roman Church is surprising, and it's hard to understand how knights who are said to have defended for nearly two centuries the interests of the Catholic Church in the Holy Land could hold such a position.

In Article 8 of the Rule of the Consoled Brothers of 1240, we can also read:

"There are Elected brothers and Consoled brothers throughout the world. Where you see tall buildings built, make the signs of recognition and you will find many righteous men, with the knowledge of God and of the Great Art. They have received it from their fathers and masters and are all brothers. Among them are: the Good Men of Toulouse, the Poor of Lyon, the Albigensian, those near Verona and Bergamo, the Bajole of Galicia and Tuscany, the Beghards and Bulgarians. You will lead them to your chapters by underground passages and for those who are fearful, you will give them the Consolamentum outside the chapter before three witnesses. " 17

The Secrete Rule of the Knights Templar seems to welcome everyone except the good Catholics. With such a content, it is quite understandable that the rules were declared as a crude forgery. There may be however a rather simple explanation for it. If Master Roncelin was indeed a Provençal knight writing in 1240, the historical context of Provence in the first half of the 13th century may well justify the aggressive tone of the Hamburg documents.

Provence, land of the Holy Roman Empire

Indeed, in that time, the Provençal nobility hadn't forgotten the Roman Church's hegemonic policy in the lands of Provence with the help of the King of France. In 1226, King of France Louis VIII had besieged Avignon even though it was, like all Provençal lands, on the grounds of the Holy Roman Empire. Under cover of the Albigensian Crusade, the Roman Church and the King of France had overstepped their authority in the lower Rhone Valley. The Holy See had annexed the Comtat Venaissin, formerly an Imperial land and the stronghold of the Count of Toulouse Raymond VII. The Count of Provence, Raymond Béranger V, a Catalan, joined in the scheme, taking advantage of the Capetian protection to strengthen his power over the cities of Provence.

The people of Provence had no choice but to turn to the Emperor Frederick II to defend their rights. In 1226, Pons de Fos, the eldest and head of the family of Fos, signed a pledge of loyalty to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. 18 Barral of Baux, head of the imperial party in Provence and close to the Templar house of Arles 19, who was excommunicated five times, exclaimed without hesitation: "All those who are absolved are my enemies and all those who are excommunicated are my friends." 20 - which reminds of us of the 8th article of the Rule of the Consoled Brothers. The sulfurous content of the secret statutes could be not the sign of a fraud but rather the mark of the Ghibellinism 21 prevailing in Provence in the first half of the 13th century.

the anti-clerical violence in Provence

The rancor caused by the local clergy's participation in the French crusade aroused acts of violence against the clergy in the cities. In Avignon, as in Arles in 1237, and more still in 1239-1240, the 'Patarin' troubles started again - often with brutality. The clerics were chased away, the oblations and even sometimes the offices were barred, and the imprisoned heretics were liberated.22

In 1246, Avignon took Barral of Baux for Podestà. His first measure, of symbolic significance, was to free the only citizen of Avignon which had been jailed by the bishop for heresy . Moreover, one of Barral's handymen struck a priest in religious vestments, and several 'religious sites' such as the home of St. Benezet and the Durand Uc Hospital were secularized and placed under the control of the township. 23 The Ghibelline party clearly sought the backing of the Provençal heretics to counter the ambitions of the Roman Church in the region. We can see why the Secret Statutes of Master Roncelin welcomed followers that were all but good Catholics.

The lords of Fos and Provençal politics

Roncelin de Fos, the alleged author of the secret statutes, was totally involved in this Ghibelline policy. He is named amongst the leaders of the insurrection when the town of Marseille arose against the Count of Provence's ambitions and gave itself for protector the Count of Toulouse, Raimond VII, with Emperor Frederik II's approval. The Chronicles of Provence designate Roncelin de Fos, Raimond Jauffroy and Raimond of Baux, viscounts and governors of the city, as "main leaders and key drivers of this war”.24

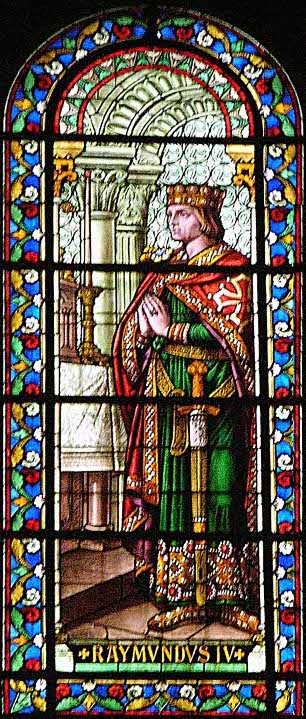

This coalition of the Viscounts of Marseille, the lords of Baux and of Fos behind Raimond VII, Count of Toulouse, reminded the Provençal of the Mount Pligrim's oath. In 1103, during the First Crusade's siege of Tripoli, the Count of Toulouse Raymond de St Gilles had asked all the Occitan and Provençal present and with whom he had then founded the County of Tripoli to pledge their alliance to his dynasty.

Amongst the Provençal men who swore loyalty to the Count of Toulouse were the Viscounts of Marseille, Raimond de Baux and three sons of Garcia : Pons, Gaufrey and Bertrand , lords of Fos, of Aix and of Hyères 25 . The Provençal remained faithful to their oath taken in the Holy Land up to the end of their dynasty in 1249.

Roncelin de Fos, master of Tortosa

The county of Tripoli stayed in close relation with the counts of Toulouse and Provence. In 1142, Count Raymond II of Tripoli, a cousin of Alfonso Jordan, Count of Toulouse, entrusted the defense of the county of Tripoli to the chivalry of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem. 26 This knighthood settled its Grand Priory in St Gilles du Gard, a possession of the Counts of Provence which is also at the origin of the patronym of Raimond de Saint-Gilles, Count of Toulouse. Raimond de Saint-Gilles also donated to the famous Benedictine abbey of Saint-Victor of Marseille half of the city of Gibellet situated between Tripoli and Beirut. 27

The close links between Provence and the County of Tripoli also explain why Roncelin de Fos, present in 1242 at Tortosa, the chieftain house of the Templars in the province of Tripoli, seems to have been Master of this Province. 28 His ancestors participated in the founding of the County of Tripoli. 29

The Provincial House of Tortosa is located at the border of the territories controlled by the Muslim sect of the Assassins. Throughout the twelfth century, this sect paid a tribute of two thousand bezants to the Templars, which an emissary brought annually to the Templar House of Tortosa. 30 It is in these same Lebanese mountains overlooking the County of Tripoli that one could encounter the Druze. Roncelin de Fos , having been Master of the Province of Tripoli, was bound to know them and it is hardly surprising that he wrote in Article 9 of the Comforted Brothers : "you will receive fraternally the Brothers of these groups and, in the same way, the Consoled of Spain and Cyprus will fraternally receive the Saracens, the Druze and those who live in Lebanon." 31

The career of Master Roncelin de Fos

We can see from a closer look at the career of Roncelin de Fos, 32 that he was an important Templar figure. Master of the Province of Tripoli, Master in Provence and England, Roncelin held the position of provincial Master during nearly forty years. It seems that he also led diplomatic action. In 1242, his name appears in an act in Tortosa, Syria, where he settled a conflict between the Knights Templar and the Hospital. He solved another dispute between the two orders in Saint Jean d'Acre twenty years later.33

He has also traveled a lot: in Provence, in England, and in the Holy Land where, as provincial Master, he was called to form the General Chapter of the order which met periodically in the motherhouse of St. John of Acre. According to Laurent Dailliez, he also undertook a mission in Italy in the years 1263-1265. 34 Laurent Dailliez also found the name of Roncelin de Fos, listed after the one of Thomas Berard, on a safe-conduct dated October 1252 given to several persons in Palestine on their way to Tripoli. 35 The General Chapter held the same year at St. Jean d'Acre, probably before October 1252, may well have witnessed Thomas Berard 's election as Grand Master.

seal used by Roncelin de Fos

The presence of the names of Roncelin de Fos and Thomas Berard on a same document can be explained. Some historians say Thomas Berard was an Englishman.36 Now, Roncelin de Fos was Master of England in 1252. If Thomas Berard represented the English party in the Knights Templar's chapter, it is logical that Roncelin de Fos supported his candidacy. This also reminds us of the declaration made by the preceptor of Aquitaine Geoffroy de Gonneville who designates Master Roncelin and Thomas Berard as those who have brought the bad and perverse statutes within the Temple. The involvement of the English Templars in this sorry affair was closely linked to political choices of the King of England himself.

The stakes of the Knights Templar's policy in the West

Since the Grand Master William of Chartres (1210-1219), the ruling body of the Templar order followed faithfully the policy established by the Roman Church. During the first phase of the Albigensian Crusade, conducted on lands of the Count of Toulouse by Simon de Montford, the Templars provided important logistical support to the crusaders from the North .37In the same way, the King of France granted full powers to a Templar , brother Evrard, in 1226, during the siege of Avignon, to receive on his behalf the submission of the City of St. Antonin in Rouergue 38. We can also see the Templars Grand Master, Pierre de Montaigu (1219-1232), oppose himself violently to the Frederik II's policy in the Holy Land 39 after his excommunication by Pope Gregory IX in November 1227.

But the papal policy like that of the Templars was wrong to rely too exclusively on the French monarchy, which thwarted the plans of King Henry lII who was determined to claim back from the Capetian dynasty all the territories lost by his father John Lackland.

In the forthcoming conflict, the control of the powerful network of commanderies built by the Order of the Temple in the West, which had served the French during the Albigensian Crusade and the Church in Sicily 40 against Frederick II, soon became a major strategic issue.

1240: a new Temple in England

In September 1232 a meeting was held in Bordeaux between King Henry III of England, the Count of Toulouse and marquis of Provence, Raymond VII, and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II.41 This meeting laid the groundwork for an anti-French coalition, with for main objective the reconstruction of the old Plantagenet empire. No doubt the Templars position in this endeavor was a major issue .

The problem was that the Count of Toulouse and the Emperor Frederick II had both undergone excommunication, and had many enemies among the Templars. The King of England was the only one in a position to involve the Templar Order in his policy. In 1236, brother Robert of Samford was given by Henry III the mission of escorting from Provence Eleonor, one of the four daughters of the Count of Provence and future wife of the king. 42 If Henry III and his allies had influence on some provincial chapters of the order, they were outnumbered in the General Chapter which remained in the hands of the Capetian party.43 The Knights Templar's commitment to the coalition had no chance of success without the backing of the Church.

But with the second excommunication of Frederick II, 20 March 1239, the course of events fastened. A mortal struggle between the Roman Church and the Hohenstaufen dynasty ensued this second censure. The allies became radicalized once they lost all hope of rallying the papacy to their cause. In May 1240, on Ascension Day, the King of England, attended by a crowd of lords, inaugurated a new Temple in London. The English Knights Templar had enlarged their house and got into the habit of it calling New Temple .44

At the same time, in spring 1240, at the request of Frederick II, Raimond VII and Barral of Baux resumed hostilities in Provence. They confiscate the Church's assets in Avignon, Vaison and Cavaillon. 45

It is in this climate that the Ghibelline party set up a hidden policy with the writing of the secret statues of the Knights Templar. After the final excommunication of Frederick II, this policy aimed to drive a part of the powerful Templar network away from the influence of the Roman Church and its ally the King of France.

The allies defeated

The defeat of the English armies at the Battle of Taillebourg in 1242, then the dethroning of Emperor Frederick II in 1245 by the Council of Lyons ruined the hopes of the allies. In spite of all, Barral of Baux, in Provence, put up some resistance. In 1246, he led a coalition of Provençal cities including Avignon, Arles and Marseille, and opposed himself to Charles of Anjou, brother of the King of France who had justed married - thanks to the good offices of the Roman Church - Beatrice of Provence, the youngest daughter of the Count of Provence and sole heiress of the county. In his fight against the French, Barral of Baux had in 1248 the support of Roncelin de Fos - who was at that time appointed Master of the Temple for Provence. Alas, the death of the Count of Toulouse in 1249, then of Frederick II the following year, forced Barral to submit to the French in 1250. As for Roncelin de Fos, he left for London to take up his duties as Master for the Province of Britain.

The defeat of the Anglo-Germanic alliance was complete. Ten years after their writing, the secrets statutes had become aimless. Master Roncelin's writings would probably have fallen into oblivion without Saint Louis's major political blunder against the Templars.

1252, a new Master for the Temple

Between March 1251 and May 1252, during the seventh crusade undertaken by St. Louis, the Grand Master of the Templars, Renaud de Vichiers (1250-1252), took it upon himself to initiate secret talks with the Emir of Damascus, Al-Nasir Yusuf. When Renaud de Vichiers opened up to the king for his approval, St. Louis was deeply angered because he was negotiating a truce with the Mamluks of Egypt, in which Jerusalem would be given back if the French gave up all alliance with the Ayyubid of Damascus. To punish the Templar for their insubordination, St. Louis decided to humiliate them publicly. In front of his entire army, he made the Grand Master and the Templar knights parade without chausses, accompanied by the Damascus emissary. Then Renaud de Vichiers and his brothers had to kneel before the King and admit their guilt. The Grand Master, addressing the Damascus emissary, confessed publicly that he had done wrong and that he regretted having negotiated these agreements. 46

The humiliation inflicted by the King of France was unacceptable for the Templars. The Grand Master was dismissed and replaced by Thomas Berard. This was an unexpected streak of luck for the English party which was in a state of collapse. Renaud de Vichiers was close to the King of France 47whereas Thomas Berard resumed Henry III's policy when he became Grand Master. His election probably took place sometime between January and October 1252. 48

It may be noted that, in the Hamburg documents, the rule of the Elected Brothers, approved by Roger of Montagu, preceptor of Normandy, is precisely dated August 1252 and that Normandy was part of the territories Henry III reclaimed from the King of France. The articles of the secret Rule were presumably introduced within the order during Thomas Berard's Mastery, as Godeffroy de Gonneville, preceptor of Aquitaine and Poitou, said in his testimony.

Conclusion

We believe that the Hamburg documents should be reconsidered. Contrary to what has been written so far, nothing allows us to state that the secret statutes published by Professor Merzdof are forgery.

The study of the historical context, on the contrary, supports the authenticity of these documents. It's hard to believe that a forgery of the 19th century can be based on facts that contemporary historians are only beginning to rediscover hundred and thirty years later. Historical data also allow us to characterize these documents. The 'Ghibelline' trait of the secret statutes explains in part its aggressive tone towards the Roman Church.

The content of the articles of these statutes is still to be discussed, such as the famous Baphometic figure - which wasn't peculiar to the Templars. The Baphomet took its origin in the Benedictine symbolic tradition, in which the figure was revealed to the contemplative monks only. It entered the Knights Templar via the liturgy of the canons regular which the knighthood's Rule required them to follow.

The overall structure of the secret statutes seems to link with the monastic tradition of the Strict Benedictine Observance, these 'sons of the valley', so dear to St. Bernard. 49 The Templar practices are not to be sought amongst those of heretics, as King of France Philippe the Bel tried hard to lead us to believe, but rather in the monastic Benedictine tradition – with, indeed, a good share of Ghibelline anti-clericalism .

From this point of view, the secret statutes of the Templars are a real break with the sacerdotal vision of the world embodied by a monarch of divine right such saint Louis. One senses that this break in the Temple has to do with a particular monastic ideal. On this matter, we have noted the following anecdote: in 1214, a man by the name of Roncelin de Fos "who had become a monk because of financial difficulties but, soon tired of the monastic rule, even though it didn't hinder much on his way of life, had resumed secular life, boldly sold his property for the second time in order to meet his new spendings ." 51 If Roncelin de Fos had been a monk in his youth- which is quite possible if we grant the fact he could have lived over 80 years - that would explain his mastery of Latin and his knowledge of certain mysteries. Master Roncelin, before being a rebel, had tasted the bread of the angels.

Link to theSecret Statues, in the French abridged version of Rene Gilles

by Jean-Pierre SCHMIT

Notes

1. Dr. Merzdorf; Die Ordens der Geheimstatuten of Tempelherren; Halle, 1877

2. According Merzdorf, documents are listed as follows: Archives of the Vatican, Acta inquisitionis contra ordinem militiae templi. ; Codex XV, XIV codex, codex XXXI, XXXII codex

3. In 1785, Frederick Münter discovered in Rome at the Lincei Academy a manuscript of the rule that comes from the Temple Library Florentine of the Corsini Princes. Münter published a summary in German of this rule; F. Münter; Statutenbuch of Ordens der Tempelherren, Berlin 1794

4. Hans Prutz; Geheimlehre und geheimstatuten of Temelherren Ordens, Berlin 1879

5. Rene Gilles, Are the Knights Templar guilty? Their history, their rule, their trial, Henry Guichaoua; Paris, 1957

6. Jules Michelet, The Trial of the Templars, Paris, 1841-1851, 2 vols.; Reed.: Editions of CTHS, 1987, Volume II, p. 400

7. Ibid, Volume I, p. 418

8. 1285: the date was corrected by Alain Jacques de Demurger in Molavi, The twilight of the Templars, ed. Payot, Paris, 2002, p. 82

9. I do not know who first identified Roncelin de Fos with Master Roncelinus Fos, perhaps Gerard de Sede, The Templars are among us, ed. J'ai Lu, 1962; p. 140

10. Stories of Benjamin of Tudela presented by Joseph Shatzmiller; in Pilgrimages and Crusades, Stories. Chronic and travel to the Holy Land `XII-XVI centuries, ed. Robert Laffont, Paris, 1997, p.1312

11. The lords of Fos of the house of Hyères perpetuated the surname of Roncelin for several generations until the fifteenth century, which does not facilitate the historians work .

12. H. Gay, Y. Grava, JM Paoli, AM Hale, History of Fos-sur-Mer, ed. EDISUD: Aix-en-Provence, 1977, p. 66

13. extracts Chronicle Provence in Jehan de Nostradamus, The lives of the most famous and ancient Provencal poets; new edition prepared by Camille Chabaneau and published with introduction and commentary by Joseph Anglade, ed. Honore Champion, Paris, 1913, p. 227

14. Leonard EG; Gallicarum militiae Templi Domorum; Paris, 1930, p. 27 See also Lawrence Daille, Paul St. Hilaire, Jean-Luc Alias

15. In the current research, the time bracket for Robert de Samford's career as master of the province of England is very broad. It goes from 1229 to 1248, then 1259. This scope must be corrected and clarified. See Thomas W. Parker, Charles G. Addison, Jean-Luc Alias, Paul St. Hilaire 16. Rene Gilles, op. cit, p.65

17. Ibid, p.74

18. History of Fos-sur-Mer, Op. cit., p. 69

19. In 1243, Barral of Baux founded a chaplaincy in the house of the Temple of Arles for the repose of the souls of Hugh and Barral, his father and mother. Before that, in 1234, the Temple of Arles had paid Barral of Baux 200,000 sous after the sale of estates. Same operation in 1240 with 43,000 sous forthe sale of the villa Méjanes at the Temple of Arles. Florian Mazel; The nobility and the church in Provence, late tenth-early fourteenth century, the example of families Agoult-Simiane, leases and Marseilles; CTHS Publishing, 2002, p. 465 It seems that in the years 1230-1240, the Templars of Arles helped to finance the military campaigns conducted by Barral against the Roman Church and its allies.

20. Ibid, p.414

21. 'Ghibelline': name given to supporters of the Germanic emperors of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, opposed to 'Guelph' supporters of the Popes and Italian independence.

22. Jacques Chiffoleau, "the Ghibelline of the kingdom of Arles. Notes on imperial realities in Provence in the first two thirds of the thirteenth century" in papacy, monasticism and Political Theories, Volume II: Local Churches; history collection and 'Medieval Archaeology -1, 1994, p.688

23. Florian Mazel; The nobility and the church in Provence, op. cit., p.413

24.The Chronicles of Provence were published by César Nostradamus, but in fact the notes were compiled about 1575 by his uncle John de Nostradamus (1507-1577), prosecutor in the court of parliament of Provence, brother of the famous astrologer Nostradamus . In his notes, Jehan gives the date of 1237 for events on Roncelin de Fos. Now the two Marseille uprisings we know of and which oppose the people of Marseille to the Count of Provence date from 1230 and 1236. It is possible that Jehan de Nostradamus confused the dates and that the same confusion is in the historian Anthony Ruffi's History of the City of Marseille 1696,who puts in 1237 an act of alliance between the city of Marseille and Raimond VII - which actually dates from November 1230. If the date of the Marseille revolt which Roncelin de Fos was involved in should be brought back to 1230, it could match with Laurent Dalliez's claim that Roncelin de Fos was master in England in 1236. In this case, Roncelin de Fos would have been the superior of Robert de Samford – who bears the title of procurator in the secrete statutes in 1240.

25. History of Fos-sur-Mer, Op. cit., p. 58

26. Bertran de La Farge; Raymond VI, the excommunicated Count, ed. Loubatières, 1998, p. 26

27. Regine Pernoud; Essay on the history of the port of Marseilles, from its origins to the late thirteenth century; thesis for the doctorate, Faculty of Arts, University of Paris 1935, p.72

28. Jean-Lue Alias; Acta Templarorium or Templar prosopography, ed. The three spirals; 2002, p. 181 June 17, 1242, Roncelin de Fos is named in an arbitration award between the Temple and the Hospital with the title of master of the house of Tortosa.

29. The name of Geoffroy de Fos can be seen Article 126 of the Retraits (additions to the original statutes) of the statutes of the order of the Temple. It is possible that this member of the Fos family was in 1252 the commander of the province of Tripoli.

30. Alain Demurger; Templars, a Christian chivalry in the Middle Ages, ed. Du Seuil, Paris, 2005, pp. 349-350

31. Rene Gilles, Are the Knights Templar Guilty?; Op. cit., p.74

32.In the current state of research, our knowledge of the career of Roncelin de Fos becomes clearer after 1242. Before that date, he may have been master in England in 1236 according to Laurent Dailliez; Templars in Provence-Alpes Méditerranée ed., 1977, p. 293

33. J. L. Alias, Acta Templarorium, op. cit., p. 181

34. Laurent Dailliez; Templars in Provence, op. Cit., P. 293 Unfortunately, Laurent Dailliez does not give his sources for the career of Roncelin de Fos. He is certainly one of the first to offer a preview.

35. Ibid, p.293 This safe-conduct issued by Thomas Berard is also cited by René Grousset; History of the Crusades, op. cit., Volume III, p. 553

36. According to historians, Thomas Berard is said either to have been British or Italian. In 1200, there is a Thomas Berard, master in England. Perhaps an ancestor of our Grand Master?

37. Raimonde Reznikov, Cathars and Templars, ed. Loubatières, 1993, pp. 8,17,20,21 Whether in the Villedieu, diocese of Albi, in Narbonne in 1212, in Montpellier in 1215, Templar commanderies served faithfully the Church and the Crusaders from the north. Even the own brother of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse , Baudoin of Toulouse, affiliated to the Knights Templar Order , betrayed his brother in 1211 for his worst enemy, the leader of the Crusaders, Simon de Montfort.

38. Ibid; p. 13

39. See Rene Grousset; History of the Crusades and the Frankish kingdom of Jerusalem, ed. Perrin, Paris, 1991, Volume III, p. 320

40. During the stay of Frederick II in the Holy Land (1228-1229), Pope Gregory IX launched a crusade against his possessions in Sicily led by Jean de Brienne. We do not have details of the involvement of Templar commanderies during the conflict but after the failure of the Sicilian crusade in 1231, Gregory IX asked Frederick to return seized property to the Templars. See Alain Demurger; Templars, a Christian chivalry in the Middle Ages, op. cit., p. 371

41. Jean-Luc Dejean; Quand chevauchaient les comtes de Toulouse (1050-1250), ed. Fayard, Paris, 1979, p. 364

42. Great Chronicle of Matthew Paris, trans. By A. Huillard-Bréholles, ed. Paulin Paris, 1840, Volume V, year 1236, p. 131 In these chronicles, Robert de Samford is qualified as a master of the Militia of the Temple in 1236, but the writers are not always well-informed about the titles held by the dignitaries of the Temple at the exact moment the events. Robert de Samford was master for England but the chronicler may have given this title a posteriori.

43. The general chapter of the order was the highest governing body of the Temple. Its power was greater than that of the Great Master - hence the interest of its control, namely to be able to influence the appointment of various officials in the provinces of the order.

44. Great Chronicle of Matthew Paris, op. cit.; year 1240; p. 14

45. Florian Mazel; The nobility and the Church in Provence, op. cit., p. 409

46. Rene Grousset, History of the Crusades, op. cit., Volume III, p. 510

47. In 1250, the Grand Master Renaud de Vichier, a knight from Champagne, was the godfather of John Tristan, eldest son of the king of France.

48. Laurent Dailliez gives the date of January 1252 in Rule and Statutes of the Order of the Temple, ed. Dervy, Paris, 1996, p.27, footnote 8

49. The valley, symbol par excellence of the Cistercian monks of the Strict Observance Benedictine, will become a must for medieval knights seeking the Holy Grail, as Perceval (literally 'that which passes through the valley') or Parzival for the German, or Perlesvaux for English.

50. The theory of a Cathar thought within the Temple has been, I believe, over-focused. In fact, as stated in Article 8 of the Consoled Brothers , the 'consolamentum' given to some recruits was a way to reassure those heretics who feared to engage in an order reputedly excessively Catholic. This was primarily motivated by political objectives rather than by a religious obligation. The sources of the Liber Consolamenti are rather to be sought in the Liber ad milites Templi of Saint-Bernard, where one can read: "As a mother comforts her son, I also will comfort you, you will be comforted in Jerusalem. " (chapter 111.6), or "if only we have the certainty of belonging among those whom the Apostle speaks in these terms: 'He chose us in him' - no doubt it is the Father who chose us in the Son "(chapter XI, 24), Bernard of Clairvaux, In Praise of the new chivalry, Christian Sources No. 367, Editions du Cerf, Paris 1990

51.Alphonse Denis, Hyeres ancient and modern, ed. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseille, 1999, p. 24